Monitoring Online Discourse During An Election: A 5-Part Series

The advantages of managing election logistical issues through social media.

Organizing the logistics of an election is a complex process. It’s a question of scale; the sheer numbers involved – of voters, of polling options and locations, and of election materials – means that things can, and will, go wrong.

POTENTIAL OPERATIONAL ISSUES

- Delay in receiving ballots in the mail

- Questions about options of voting electronically or by mail

- Incorrect name or address on ballot

- How to find information on where to vote

- Confusion regarding polling station location

- Confusion regarding the hours that polling stations are open

- Accessibility issues

- Confusion regarding what ID to bring

- Power outages that impact polling stations

- Road blocks and construction impeding access to a polling station

- Whether polling hours are delayed

- Whether there is a long line-up and voting is delayed

- Availability, and courtesy, of EMB personnel

- Conflicts at the polling station

- Issues re third-party election monitors (if applicable)

- Police presence

- Dead people and non-citizens voting

Operational issues can be divided into two types. There are logistical concerns, such as:

- Too few Electoral Management Body (EMB) staff, or not enough ballots

- Localized influxes of people causing bottlenecks at particular polling stations

- Power outages

As well, there are problems caused by the propagation of disinformation (or misinformation).

What role is played by Disinformation?

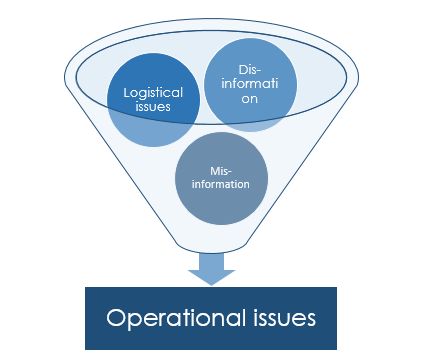

There can often be an overlap between Operational Issues, Disinformation, and Misinformation. Tweets regarding the location of a particular polling station fall into the Operational Issues category, but that information may be mistaken (Misinformation) or deliberately misleading (Disinformation). There is an almost complete overlap between Disinformation and Misinformation – the only difference is the intent behind the sharing of inaccurate information.

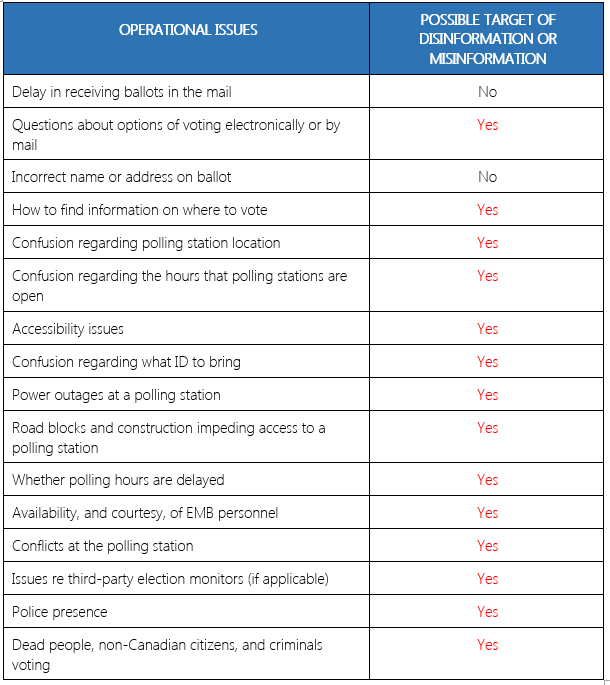

As the table below demonstrates, many Operational Issues may also become targets of Disinformation or Misinformation.

Why should EMBs monitor social media?

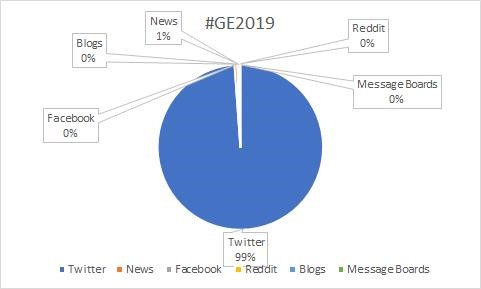

EMBs have a formal complaints process, and if concerns are raised outside that process, EMB staff are not obligated to respond. However, given the pervasive nature of social media, vexed voters are much more likely to grouse on the Internet than to file a formal complaint. Social media has become an informal complaints process; Twitter in particular. With its use of hashtags, Twitter dominates social media election discourse. (Election discussion on Facebook, Telegram, and WhatsApp takes place on private pages.) The chart below shows social media discourse around the 2019 UK general election with the hashtag #GE2019, by volume.

What can EMBs do about social media-based complaints?

Complaints can fall into one of several categories:

- Individual: An individual tweets that they are having trouble voting; for example, “They wouldn’t let me vote with my ID.” The EMB can respond with a (personalised or public) tweet giving information, and/or contact the complaints officer at that polling station on the person’s behalf.

- Public: These issues may be something the EMB can mitigate (sending more ballots to a polling station, for instance), or something that the EMB can manage but not mitigate (for example, giving out information about a power outage in the region and its impact on the voting process).

Social media as a mass communication tool: Social media messaging can mitigate public discontent, respond proactively to problems, and send broad messaging demonstrating that the EMB is in control of the situation. For example: after complaints of robocalls which state the election date has changed, the EMB could tweet that these robocalls are giving false information and should be ignored. Such messaging will be picked up by traditional media.

- Candidate/Party-related: Parties or candidates may raise complaints that they have been unfairly disadvantaged; for example, that an opponent is launching a disinformation campaign. (Once instance: A political party complained that a competing party published an inaccurate article in a media outlet of a neighboring country, and that it had received a lot of attention. The EMB investigated the existence of the article and, using social media, the impact it may have had on the outcome of the election.)

- Logistical (internal): Monitoring can be used internally by the EMB:

- To capture environmental factors that could influence the volume and timing of voting; for example, a polling station close to a factory will have different peak voting times than one in a suburban area.

- For future reference: Lessons learned can be incorporated into the training of staff, support staff, media monitoring staff, and poll workers.

- As evidence: Social media participation data can be helpful in responding to criticism, by demonstrating that the EMB has been doing its job.

When should EMBs monitor social media?

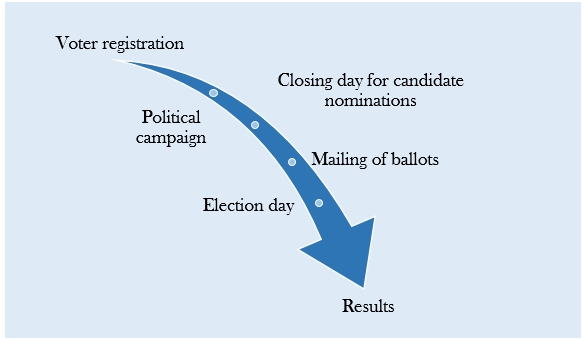

Monitoring should occur throughout the election period, Election milestones tend to be flashpoints when online discourse increases – these are highlighted in the diagram below.

Part of a 5-part series on

Monitoring Online Discourse During An Election:

PART TWO: Identifying Disinformation

PART THREE: Managing Operational issues

PART FOUR: KI Design National Election Social Media Monitoring Playbook