Disinformation campaigns and the future of elections

United States citizens are still recovering from the aftermath of the election. KI Design’s media monitoring data shows that 39% of online election sentiment is negative. Voters have experienced sustained disinformation campaigns that have compromised the electoral system and undermining public confidence in democratic processes.

Disinformation – false information spread with the intent to deceive – can be usefully compared to pollution entering a river. Once it’s out there, the impacts remain, and it continues to cause damage. Like pollution, disinformation cannot simply be removed, as it will continue to flow; it needs to be stopped at source.

Disinformation is an existential threat to democracy

During the past five years, KI Design has been monitoring disinformation campaigns around elections. Disinformation often follows given patterns:

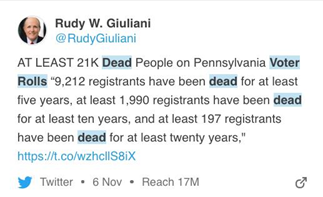

- Voter eligibility and claims of fraud; for example, dead people, prisoners, or illegals voting.

- Ballot issues and claims of fraud; for example, ballot theft, delays, addressing errors, or fake ballots.

- Impersonation of candidates or fake claims on their behalf.

- Polling station issues: Location change, time change, fights, or staff bias.

- General unsubstantiated claims of political bias, etc.

In the build-up to the 2016 US election (and the Brexit vote in the UK), many sophisticated disinformation campaigns were tracked back to foreign (primarily Russian) sources.

During the 2019 Canadian elections, disinformation came from un-identified sources; individuals hiding behind fake online identities. A large portion of the disinformation pollution came from less than 50 Twitter users. Many of these accounts have now been shut down.

Since then, however, the political landscape has shifted dramatically. Now disinformation is perpetuated by top US government officials, such as Rudy Giuliani.

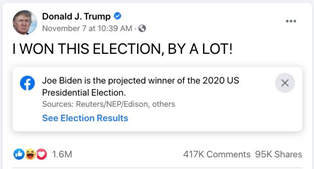

Much also stems directly from the White House. As Julia Carrie Wong commented in the Guardian: “what kind of false tale of voter fraud could Iran possibly seed that could undermine Americans’ faith in the electoral process more than the disinformation about voter fraud and mail-in ballots coming straight from the White House and Trump’s campaign?”[1]

Disinformation can be direct: a clear statement of a falsehood. For example, President Trump:

- stated in the months before the election that mail-in ballots are fraudulent.

- stated after the election that because mail-in ballots are fraudulent, they shouldn’t be counted.

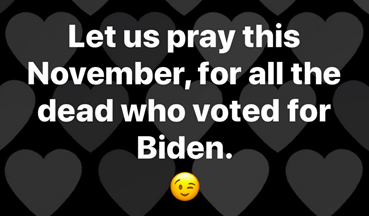

It can also be expressed indirectly. For example, it could take the form of:

- Images or videos (tampered with or used out of context)

- Jokes or memes

These similarly have the effect of creating a climate of cynicism about the political process.

Unless disinformation can be eradicated at source, by making the intentional dissemination of falsehoods illegal, democracy will continue to be undermined.

How can disinformation be dealt with?

There are three ways our governments can respond to disinformation.

- Do nothing:

Most people would agree that, post-2016, “do nothing” is not a viable option.

- Press for a stronger response from social media platforms:

- Independent actions – during the 2020 US election, internet platforms flagged content that they considered to be disinformation. Twitter has been the most proactive of the major platforms. In the two days after the November election, Twitter labelled 38% of President Trump’s tweets with warnings of misleading claims.[2]

Facebook is also increasing labeling of false or disputed information.There is, however, a risk that platform labeling could become the equivalent of cigarette advertising. People see the negative labelling, but effectively ignore it.

- Create an industry-led consortium and disinformation Code of Conduct. However, past events (the Cambridge Analytica scandal, for example) suggest that social media platforms may not be up to the task of regulating themselves.

- Active monitoring by election management bodies:

Electoral management bodies in the US and Canada have monitoring oversight powers, but they have little or no policing ability. Their hands are tied. They can’t impose penalties on individuals or groups who spread false information with the intent to deceive.

There are currently no legal penalties for spreading disinformation

Electoral management bodies should be given teeth. They need a clear mandate, with powers to impose fines and imprison those who intentionally and repeatedly undermine the electoral process, and disqualify offenders from standing in elections.

As well, staff at electoral management bodies need to be thoroughly trained in the use of sophisticated web-monitoring tools, and in the impact of social media disinformation campaigns on the electoral process.

—

The data and analytics in this article are provided by KI Social

[1] Julia Carrie Wong, “’Putin could only dream of it’: how Trump became the biggest source of disinformation in 2020,” The Guardian, 2 November 2020, online at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/nov/02/trump-us-election-disinformation-russia.

[2] Kate Conger, “Twitter Has Labeled 38% of Trump’s Tweets Since Tuesday,” The New York Times, online at: https://www.nytimes.com/live/2020/2020-election-misinformation-distortions#donald-trump-twitter.